Figure 1: Jobs created per $1 million invested

As a research-driven investment house, identifying, analysing and understanding the trends and changes that impact, or will impact, our investments is at the heart of our “thematic” research focus. It was in that context that a recent UK report entitled “Getting to Zero”1 caught our attention. It has been cited under press headlines suggesting that as many as 10 million UK jobs would be at risk from the UK’s transition to net zero over the next three decades. Is that really the potential implication of the UK’s decarbonisation plan? We think not.

Will net zero boost employment growth?

Current longer-term employment issues do need to be considered in the context of an “industrial” revolution that is already playing out and likely to be accelerated by the effects of the coronavirus pandemic. Digitisation and automation are examples of this and more than 80% of CEOs surveyed by the WEF3 reported that they are accelerating the automation of their work processes and expanding their use of remote work. That has implications for employment, but not the way some people think. Let’s start with some context on climate change:

Framing the scale of the economic challenge4 Scientists have estimated that were temperature increases to reach three degrees celsius global GDP would fall 25%. If they reached four degrees the decline would be more than 30% compared to 2010 levels. That is comparable to the Great Depression, but the difference is that the impact would be permanent.

In terms of employment, the associated upside growth in EU employment is, at the more conservative end of the scale, around 0.5%. That is approaching an extra million jobs compared to business as usual. The employment implications do vary by country, as well as by sector6:

- Services sectors, for example, benefit from both increased consumer activity but also as part of the supply chain of renewables and energy efficiency equipment and installation processes. This reflects a strong trend we were seeing in the US before the Paris Agreement withdrawal.

- In contrast, the mining sector faces a substantial fall in employment reflecting lower production in the energy extraction sector.

- The implications are, of course, not just for employment but also countries’ economic competitiveness.

Figure 2: EU employment growth projections by sector

2030 (%) | |

|---|---|

Agriculture | 0.5 |

Mining | -16.6 |

Manufacturing | 0.7 |

Utilities | -2.4 |

Construction | 1.1 |

Distribution, retail and hotels and catering | 0.6 |

Transport and communications | 0.5 |

Business services | 0.7 |

Non-business services | 0.3 |

Source: FOME energy scenario projections, 2020

However, under the same analysis the US’s outlook under the Trump administration, having rejected the Paris Agreement, was not looking so rosy. That stood in stark contrast to what we were seeing ahead of the then president’s announced withdrawal from Paris. Compared to the EU’s 1.1% boost to GDP, the US faced an estimated 3.4% contraction in GDP by 2030 and a 1.6% hit to its job market.7

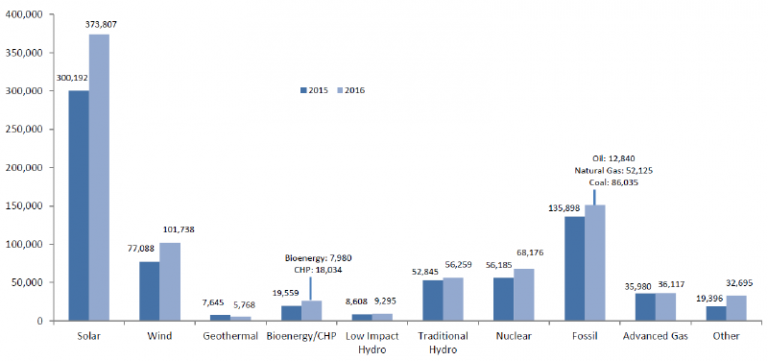

Figure 3: Electric power generation employment by technology (Q2 2015-Q1 2016)

Source: US Department of Energy, US Energy and Employment Report, January 2017

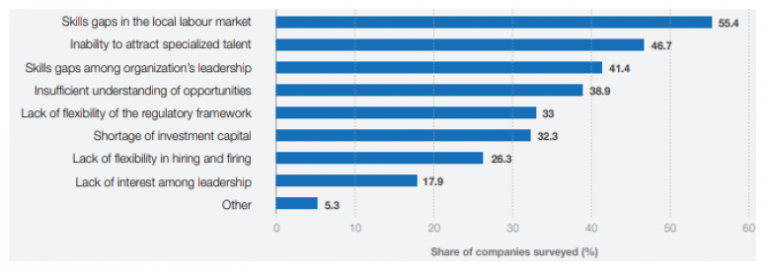

The UK’s adoption of climate-relevant approaches as part of a strategic approach to economic stimulus and recovery11 will have important and positive implications for both job creation and long-term competitiveness. As part of this, the need for policymakers to embrace “inclusive growth”, taking account of the trends playing out, should not be underestimated. The rebalancing we expect to see in the jobs market will make active labour market policies (ALMPs12) an important focus for policymakers. The need for, and merit of, initiatives such as the EU’s Skills Agenda13 is clear. In laying the foundations to support future competitiveness and address key challenges, the World Economic Forum’s work highlights some of the challenges policymakers need to consider (Figure 4).14

Figure 4: Perceived barriers to the adoption of new technologies

Source: WEF, Future of Jobs Report 2020, October 2020

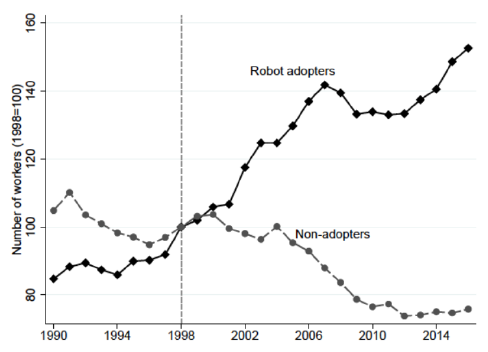

The WEF estimates that by 2025 85 million jobs may be displaced, while 97 million new roles may emerge across the 15 industries and 26 economies it examined – a net gain of 12 million jobs. Education, training and the re-skilling of the workforce will be critical issues in this context. Reflecting that, corporate planning on future investment and operations will be influenced by the availability of the right skills and talent. It is not the companies that embrace change that lose out. As recent historical evidence tells us, companies that automate will survive, prosper and hire more workers. Those that don’t will end up shedding staff (Figure 5).15

Figure 5: Robots in the workplace

Source: Michael Koch, et al. “Robots and firms”, July 2019

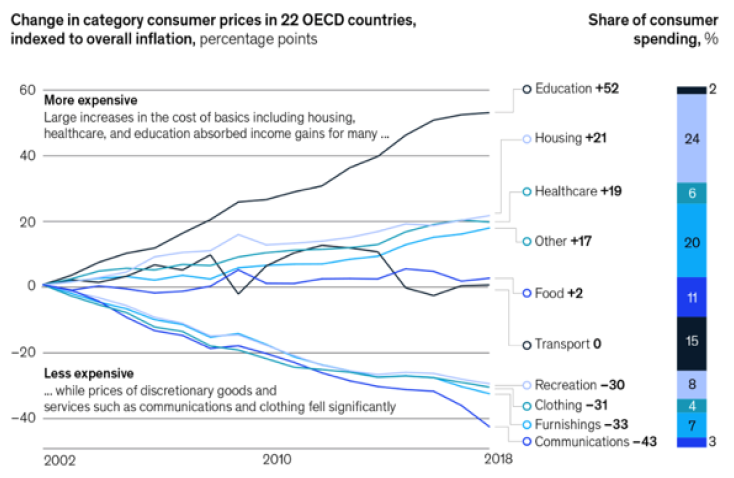

Figure 6: Consumer costs on the rise

Source: OECD, 2019